Understanding the roots of the West isn’t always what we see in Hollywood bright lights.

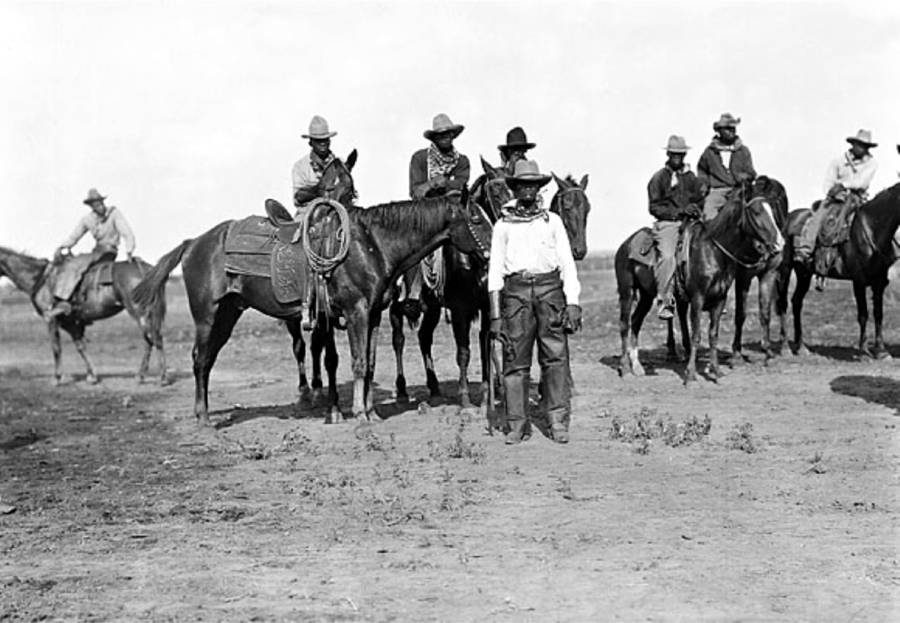

Our imaginations and fascinations run wild with images that are painted for us of what a cowboy is and does, but our imaginations have been greatly misled. Our dreams of cowboys ignore history and fail to recognize the people who are entirely responsible for creating the modern cowboy of the West: The African American Slave.

During a dark time in American history, some slaves found what little refuge there was on the back of a horse among cattle. Like many of us who enjoy riding to escape the realities of life, slaves often looked forward to spending nearly 18 hour days in the saddle herding cattle. Known as “cow boys” – two words and meant to imply a lack of manhood – slaves quickly became extremely valuable to the settlement of the South. While white ranchers were known as drovers, traders, or cattlemen, they relied on the irreplaceable knowledge of cow boys to run, care for, and manage their herds. Some land grants in the South required the presence of enslaved cow boys in order to be received, and those cattlemen with slaves were proven financially far more successful than those without.

There’s no doubt the cow boy experienced life much differently than the average field worker because of their cattle sense. Although not free men and not entirely free of the horrors and brutality of slavery, the average cow boy had more freedom than plantation slaves. Cow boys worked in wide open spaces, without supervision in remote areas of the country, often carrying a firearm.

So why didn’t more cow boys turn-tail North to freedom from bondage? It is likely that cow boys did not perceive their work to be slavery, especially in comparison to what their fellow slaves were enduring in the fields. Slave-owning cattlemen worked with their cow boys and treated them similarly to white employees. This is not to say that slave brutality did not exist, but the fact is that cattlemen learned to trust and earn trust of their most valuable hands with their most valuable asset.

When the Civil War began, many white cattlemen went to battle and left their property – both land and livestock – in the hands of enslaved cow boys. These men were often trusted to run the business over the hands of the wives, who usually did not have much of a role outside of the household and garden. Ranching was one of the few industries that successfully survived the war. This is a testament to the loyalty cow boys felt to the herd, job, and owners and demonstrates how badly the cattle industry in the south depended on the talents of the cow boys.

After the Civil War, cow boys had advantages in society that field-workers were not afforded. Not only did they have a reputation with white, land-owning men as being skilled, but their skills were consistently recognized across state lines. A black man on a horse was far more respected than those who worked on a cash-crop plantation. The cattle industry had a life post-emancipation proclamation and gave real value to cow boys looking for work opportunities outside of their bondage. Many cow boys kept their jobs and received a wage comparable to white hands during this time, while field workers struggled to survive in the South with skills that were not as valuable without the institution of slavery.

As America moved West, so did the cow boy. The trek West for the cow boy was usually under employment conditions and was used to fund their own dreams of being a cattleman one day. There is record of black cowboys taking only a partial salary in cash, with the remaining salary applied to purchase cattle for a ranch of their own. Eventually, these cow boys turned into homesteaders, who turned into ranchers with farm hands – of all colors – of their own. There were far less black ranchers than white cowboys, but their business and contribution to the industry remains of the same importance. Former cow boy John Wallace ingrained himself in his local cattle raiser’s association, earning the respect of white ranchers and created a sustainable ranch that survived World War II. One cow boy, Mathew “Bones” Hook, used his ranking among white cattlemen to become an activist for black communities. His famous ability to break a horse and manage a herd on a cattle drive earned him employment with large ranches. He continued to serve alongside white cattlemen as a charter member of the Western Cowpunchers Association of Amarillo and the Western Cowboys Association in Montana. Mathew celebrated the history of black cow boys, but also established a permanent place for them in the community by reinvesting his salary into real estate that was safe for black families to settle in.

The role of the American cow boy was and continues to be a great equalizer in our society if we choose to remember their history. Horses and cattle connected the black slave, and later black citizen, to American soil in a foundational way that we cannot ignore when recounting the development of the West. In fact, we have our early cattle herds to thank for completely rebranding black slaves into a transformative role model we allow our children of all races to look up to in this nation: the cowboy.

Listen to this article in podcast form on Episode 117, here.

Thank you to the following authors for assisting in this writing:

– Glasrud, Bruce A., and Michael N. Searles. Black Cowboys in the American West: On the Range,

on the Stage, behind the Badge. University of Oklahoma Press, 2016.

– KATZ, WILLIAM LOREN. Black Women of the Old West. Ethrac Publications, Inc, 1995.